Sports venues part of Billy Sizeler’s lasting imprint on New Orleans landscape

The Caesars Superdome recently was the site of the 90th Sugar Bowl and the New Orleans Saints’ season finale.

In between those two events the Alario Center in Westwego was the site of the Allstate Sugar Bowl National Prep Classic basketball tournament.

Over on the Tulane campus new Green Wave athletic director David Harris, new football coach Jon Sumrall and the rest of the athletic department staff are busy at work inside the Wilson Athletic Center.

Next door, baseball coach Jay Uhlman’s team is preparing for its season opener at Greer Field at Turchin Stadium.

All of this activity – and much more, some related to sports and much that is not – has taken place in facilities either designed or re-designed by Sizeler, Thompson and Brown Architects and the firm’s founder, Billy Sizeler, an Isidore Newman School graduate who studied at Tulane and other universities on his way to becoming one of the most prominent architects in the Crescent City for several decades.

“People ask me, ‘which job do you like the most?’” said Sizeler, who’s technically retired but still very active at age 84. “That’s like having three children and being asked, ‘which is your favorite?’ They’re all special for different reasons.”

The special nature of the renovation of Tad Gormley Stadium, which Sizeler and his firm helped renovate so it could host the 1992 U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials, is the architect’s personal history with the facility.

Sizeler started running track as a 4-foot-4 4th-grader at Wilson Elementary and grew into the fastest runner in the 55-inch class in New Orleans, winning dozens of medals and ribbons. He was part of an All-America 55-inch relay team.

He was attracted to the extracurricular activity because “it’s a clean thing to do; you don’t get into trouble.”

Sizeler, who also lettered in football and basketball, and his track teammates would practice in the street on General Taylor and General Pershing near Napoleon Avenue – a training ground far less glamorous than facilities he would later work on.

At Newman he often ran against taller kids in the 100- and 220-yard dashes. He would participate in meets every other Sunday at City Park Stadium under the supervision of coach Tad Gormley, for whom the stadium would later be renamed. Sizeler also competed in the broad jump and the relay.

Let’s fast forward from youngster running around City Park Stadium to the architect preparing the same facility for some of the best track and field athletes in the world.

Sizeler was with his children at the Audubon Zoo one weekend more than 30 years ago when he ran into an acquaintance who worked in City Hall.

The man told him Sizeler to call him the following Monday about “a job you may be interested in.”

Upon learning that the project was to renovate Gormley for the Trials that would determine the United States track and field team that would compete in the 1992 Barcelona Olympic, Sizeler replied, “Interested? Who do I contact?”

He called the renovation of Gormley, which was built during the Great Depression by the Works Progress Administration and completed in 1937 still hosts high-school football games regularly, “the epitome of combining architecture and sports, things I grew up with.

“I loved it from all points of view,” he added.

Sizeler said the stadium where he had learned the finer points of sprinting decades earlier “absolutely had good bones.”

The architect, who got his undergraduate degree from Brandeis University, studied architecture at the University of Pennsylvania (as well as Tulane), where he and fellow students were “enthralled” as they listened to talks from iconic architect Louis Kahn, who Sizeler called “The Socrates of Architecture” and who taught graduate architecture courses at the school.

“He would talk about, “what is a window? What is a door?’” Sizeler recalled. “What is the nature of a brick? What does a brick want to do, compared to what does wood want to do, what does steel want to do?

“What is a porch? What’s the nature of the transition from inside to outside?”

Sizeler was inspired as Kahn took “a totally different approach” to architecture.

“He influenced all the other professors,” Sizeler said of Kahn. “He influenced the whole school.”

And he influenced Sizeler, whose father was a homebuilder with the firm of Lauricella and Sizeler. Billy “liked drawing” and after taking a drawing class at Newman he started to see the possibilities in combining “artists with architecture.”

Sizeler has been involved with the design or redesign of numerous other facilities that are home to a variety of sporting events – Privateer Park and the student recreation center at UNO, the Ursulines Academy gym, phase 2 of Pelican Park in Mandeville, which features soccer and baseball fields, jogging trails and other structures, the Goldring fitness center at the Jewish Community Center on St. Charles Avenue, and the Patrick Taylor Academy activity center, which was built during COVID.

Additionally his firm designed the multi-purpose Kenner Discovery Health Science Academy Performing Arts Center and Sports Facility that is under construction.

And then there’s Tulane.

Sizeler said he was “thrilled” to design the Wilson Center in the late 1980s.

He added that he’s “very proud” of how frequently late Tulane President Dr. Eamon Kelly would find non-athletic ways to utilize the distinctive atrium at the center of the Wilson Center, which has been a symbol of the Green Wave’s decades-long efforts to modernize the university’s athletics program.

Sizeler still has a fondness for the school he attended in addition to his father graduating from Tulane, his mother graduating from Newcomb and his wife Jane working there for 22 years – and he lived within walking distance of the campus.

Tulane had long respected neighborhood residents’ resistance to night baseball – until Sizeler and his firm designed Turchin Stadium, which opened in 1991. His familiarity with the neighborhood as well as that of his wife and her family, was instrumental in getting the baseball stadium just right for all parties.

“I loved working on that job,” Sizeler said. “It was about doing more than architecture.”

Sizeler, whose non-athletic projects include the LSU School of Dentistry, Xavier’s Norman Francis Academic Science Complex addition, most of the Dillard campus both before and after Hurricane Katrina and the SUNO science building, is technically retired, but he said he stays involved by “sort of doing marketing” to help the firm continue to succeed.

“Emotionally,” he said, “I can’t give up the firm.”

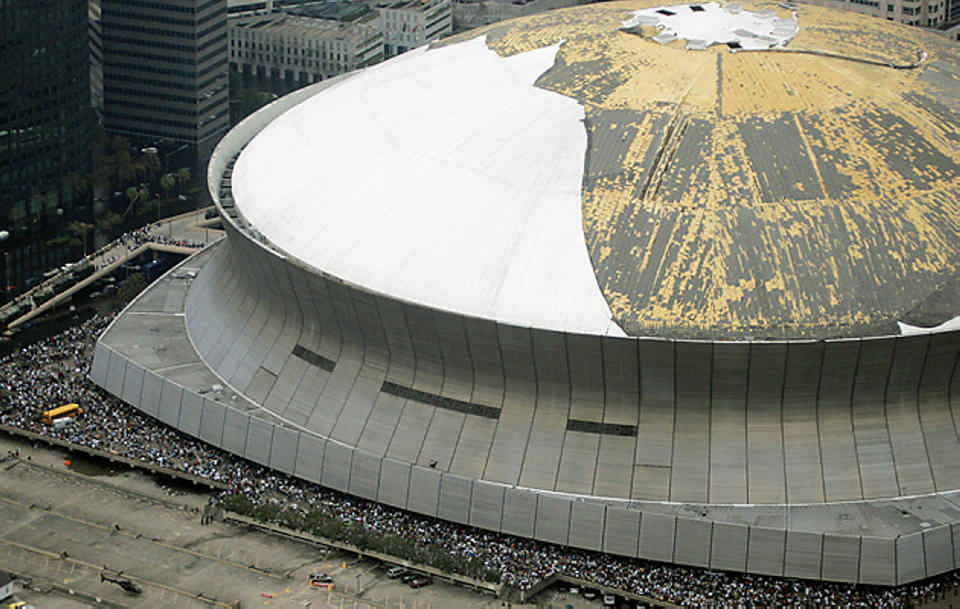

Of all of the sports and non-sports projects that Sizeler has worked on nothing else compares to the 2006 renovation of the Superdome in the wake of Katrina.

Sizeler’s firm was one of four groups that united to cram what normally would have easily taken more than a year into a nine-month window.

He called his firm “a team within a team” on the Dome project – not unlike a group of relay runners represented a track and field team.

Sizeler said the project was undertaken by “a lot of honorable people that all wanted to be successful.”

“We knew how important it was to the image of the city,” he said, recognizing that the Dome was “a symbol of New Orleans.”

The challenge required a 24/7 approach. Sizeler recalled Superdome head Doug Thornton constantly reminding everyone “failure is not an option.”

“The first thing you had to do was put a new roof on it,” Sizeler said. “That didn’t just mean this white covering. We replaced 10 acres of steel. All of the steel had rusted.”

The group responsible for fixing the roof was given six months to complete the task in time for the rest of the work to be completed in time for the Saints season opener on September 25.

“Everybody said it would take at least a year just to do the roof,” Sizeler said. “We said we don’t have a year.”

Sizeler said the project was “a dream job.”

“Everybody wanted to succeed,” he said. “We wanted the Saints to be successful. We wanted the Dome open because it would help bring back the city. It would give people something to hope for. It was such a catastrophe.”

Sizeler stepped outside his architect’s role to help raise funds to erect a gallery on the Poydras Street side of the building, chronicling the rebuilding of the Dome.

Billy and Jane were seated in a suite in the South end zone (next door to U2 and Green Day) when Steve Gleason’s iconic blocked punt took place right in front of them.

The reopening of the Dome was a turning point in the history of the Saints. The victory against the Falcons marked the first home game with Sean Payton as head coach and Drew Brees at quarterback.

That season New Orleans went to the NFC Championship Game for the first time, three years later it won the Super Bowl and a decade and a half of unprecedented success continued under Payton and Brees.

“People say it was all Drew Brees and Sean Payton,” Sizeler said. “I say it was none of them. And they say, ‘what do you mean?’ If it wasn’t for us bringing the Dome back they couldn’t have played.”

Sizeler was teasing, of course, but what he said was true.

Billy and Jane have been married for more than 60 years and have three children and five grandchildren.

Their youngest daughter, Debbie, followed in her father’s track footsteps, competing in the 100, 200 and 400 as well as the 400-meter, 800-meter and mile relays while a student at Country Day.

The appreciation for the ethereal aspect of architecture that Sizeler gained as a young architect has served him well throughout his career.

He said he has always been “devoted to the client to help in any way beyond architecture.”

“We always listened to the client very well,” Sizeler said. “We wanted to understand their dreams and wishes and bring them to life in a three-dimensional, exciting space that was visually interesting.

“If you can make the client happy, then you have a success.”

- < PREV Former LSU center Charles Turner, defensive tackle Jordan Jefferson participating in Senior Bowl week

- NEXT > UNO looks to take elusive next step under Dean

Les East

CCS/SDS/Field Level Media

Les East is a nationally renowned freelance journalist. The New Orleans area native’s blog on SportsNOLA.com was named “Best Sports Blog” in 2016 by the Press Club of New Orleans. For 2013 he was named top sports columnist in the United States by the Society of Professional Journalists. He has since become a valued contributor for CCS. The Jesuit High…