Minor league baseball is gone, but won’t be forgotten in Jefferson Parish

METAIRIE – Minor league baseball is defined by its transitory nature.

People are always coming and going – young prospects passing through on the fast track to the Major Leagues, past-their-prime ex-big leaguers trying to reverse their descent, and in-betweeners playing a big-picture version of station-to-station baseball, bouncing from stop to stop, never quite sure if they’re getting closer to or farther from the Major Leagues.

Even player development contracts designed to provide a consistent flow of talent between the farm clubs and the major league club usually feature mere two-year commitments.

Sometimes even buying green bananas can be a sign of unrealistic expectations.

New Orleans’ Triple-A franchise arrived from Denver in 1993 and now is on its way to Wichita, Kansas for the 2020 season – certainly a longer stay than the proverbial cup of coffee, but for something that was a fixture in the community just a few years ago, it’s really not that long a stay.

“It has meant less and less over time,” said Ron Swoboda, the franchise’s long-time radio analyst and former major league outfielder.

Triple-A is where the soon-to-be major leaguers and the used-to-be major leaguers cross paths most frequently. New Orleans’ franchise itself experienced both ends of that development spectrum.

It was once a young, emerging star of the highest level of minor league baseball, but is now leaving town almost unnoticed like a washed-up major leaguer reaching the end of the line – maybe a couple of stops later than he should have.

“We were one of the best franchises in America in terms of consistent performance revenue wise, attendance wise, using the facility for other things,” said Rob Couhig, the attorney and businessman who spearheaded the move from Denver, bought the team two years after the relocation, oversaw its heyday and sold it in 2002.

“You feel bad that something you worked on, that you helped to create along with a lot of people is going to go away.”

After a four-year mostly non-descript start at the University of New Orleans, the Crescent City’s franchise moved to Metairie and became a model franchise, a fresh experience that transformed into a hub of family entertainment an underdeveloped suburban area of a community best known for its world-class status as an attraction for tourists.

The team drew an average of fewer than 200,000 fans during those seasons at UNO, then drew an average of more than 500,000 for the first three seasons inside brand-new Zephyr Field on Airline Drive in Metairie. But in none of the last 17 seasons did the attendance reach as much as 400,000, bottoming out at fewer than 190,000 during the lame-duck season that just concluded.

“The last few years have been rough,” said Walter Leger Jr., one of Couhig’s partners, who remained a part of the organization until the end. “It’s painful to see the attendance so bad.”

It certainly has been a roller-coaster ride, which is appropriate given the team’s nickname upon its arrival, a moniker that stayed until the 2017 season.

When the Major League expansion Colorado Rockies displaced Denver’s Triple-A franchise for the 1993 season, Couhig convinced Zephyrs owner John Dikeou to move to New Orleans, where the team’s nickname, taken from a popular passenger train that never came near Louisiana, was a sentimental fit, matching that of a popular roller coaster at the long-gone but still fondly-recalled Pontchartrain Beach amusement park.

“By sheer coincidence it had an immediate attachment to the city,” Leger said.

Major League Baseball is America’s national pastime; Minor League Baseball at its best is America’s local pastime.

Each minor league market is a separate entity, not competing with all the other markets for a single championship like the major league franchises, but weaving itself into the unique tapestry of its particular community – a stable staple amid all the comings and goings.

“You’re able to be what I consider the front porch of the community,” said New Orleans general manager Cookie Rojas, who will remain part of the front office in Wichita. “Minor league baseball, especially Triple-A, presents a gathering place that’s affordable for the entire community. I think it’s really important for communities to have a place where they can go and relax and unwind regardless of race, gender, socio-economic background.”

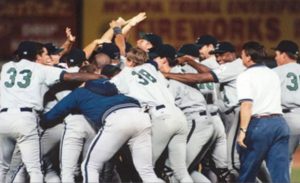

When New Orleans won the inaugural Triple-A World Series in 1998, someone posed the familiar “how does it feel?” question to Zephyrs infielder Casey Candaele.

Candaele paused momentarily before finding the precise context.

“It feels like we’re the 31st best team in baseball.”

Even the best Triple-A teams are like a really good tribute band – providing a good show and a taste of what the real thing is like but which it isn’t.

At the end of the day, a tribute band isn’t the Beatles or the Stones and even the 31st best team in baseball isn’t the Yankees or the Dodgers.

But each has its place and still can be the source of joyful memories.

The franchise known as the Baby Cakes when it played its final game Monday afternoon in Oklahoma City, is leaving behind memories and changes that can’t be measured by batting averages, won-lost records or attendance statistics.

Players too leave a mark – a hit, a defensive play, a pitching performance, game, series of games, and on rare occasions maybe even an entire season or two.

New Orleans never witnessed Mike Matheny managing the St. Louis Cardinals to the World Series but it saw him perform as an American Association All-Star catcher.

New Orleans never witnessed Lance Berkman playing in the real World Series with Houston or St. Louis, but it saw him lead the Astros’ top affiliate to that Triple-A World Series title.

New Orleans never witnessed any of Pete Incaviglia’s 1,043 hits or 206 home runs in the Major Leagues, but it saw him help the Zephyrs win that ’98 championship.

Now the baseball memories have stopped at least in part because of what former Jefferson Parish President Tim Coulon called “the continuing deterioration of the stadium.”

The building that lured the team to the suburbs has been essentially condemned by Professional Baseball pending significant and long-overdue improvements. Additionally, dwindling interest in the team, competition from the NBA that didn’t exist when the baseball franchise arrived and distant ownership haven’t helped.

Over the years there were hundreds and hundreds of baseball games, a new and unique source of family entertainment, positive economic impact and memories. Lots and lots of memories.

Baseball, unlike other sports, doesn’t play within the constraints of a ticking clock. Instead it unfolds in a series of innings, each a dramatic act unto itself but also a part of a large, more layered story.

This is a story best told in a similar manner, a series of acts recalled individually and yet within the larger narrative of all that this franchise meant to its community – and what it’s leaving behind.

Play Ball!

New Orleans is a football town that happens to have a basketball team, but baseball was grandfathered into the DNA of generations of locals long before the Saints became an NFL franchise or the Pelicans became an NBA franchise.

Barely five years after the Civil War ended, the Cincinnati Reds – the first all-professional Major League baseball organization – played exhibition games in New Orleans, and later exhibitions included future Hall of Famers such as Richie Ashburn, Bob Feller, Ralph Kiner, Ted Williams and Willie Mays.

The minor league history began with the original New Orleans Pelicans in 1887 and legends such as Dale Long, Elroy Face and Danny Murtaugh were members of New Orleans’ original minor league franchise, which mostly was the Double-A Southern Association affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Long before television or video gaming systems satisfied the appetite of fledgling sports fans, youngsters learned to love baseball while scoring Pelicans games as they watched with their family, friends and neighbors.

“Baseball makes kids out of all of us,” said Peter Barrouquere, a New Orleans native and long-time baseball fan who’s a youthful 79.

Barrouquere was the Times-Picayune’s beat writer on the Zephyrs when they arrived and covered the team for 12 seasons before retiring. He has an acute appreciation for what baseball pre- and post-Zephyrs arrival meant to this community.

He and his brother Jimmy were introduced to minor league baseball in 1952 when their father took them to a game in the now-long-gone Pelicans Stadium at the corner of Tulane and Carrollton.

“You walk into the ballpark for the first time and you smell these peanuts and popcorn is being popped and everything is so green and I had never seen lights like that in my life,” Barrouquere said. “And I said, “Man, I’m coming back.” I kept going every chance I got.”

Barrouquere said his friends generally wanted to grow up to be major leaguers, but he was different.

“I wanted to grow up to be a Pelican,” he said.

Barrouquere attended a couple hundred games before he enlisted in the Air Force and was sent to England in the late 1950s.

Initially his parents sent him newspaper clippings abroad so he could continue to follow the team. Then the clippings suddenly stopped coming without explanation.

When Barrouquere got home in March of 1961, going to a Pelicans game “was the first thing that I was going to do that spring.”

But he couldn’t wait to see the ballpark and drove to Tulane and Carrollton shortly after arriving.

“I drove over there and I saw that the stadium was gone and I broke down,” he said. “I never got over that.”

In fact, Barrouquere said, years later when he was working at the Shreveport Times and the newspaper would send him to cover a story in his hometown, it would put him up at the Fontainebleau Hotel, which had been built on the site of the stadium.

“It brought back bitter memories,” Barrouquere said.

The Fontainebleau, like Pelicans Stadium, ain’t there no more.

The void created by the Pelicans departure went unfilled for 33 years with the exception of the summer of 1977 when a Triple-A namesake of the Pelicans played inside a mostly empty Superdome.

With no team of their own to follow, professional baseball fans in New Orleans experienced a diaspora of their team loyalties.

There were Cardinals fans thanks to KMOX’s unusually strong radio signal and Reds fans thanks to WLW’s similarly strong signal. There were Colt 45s then Astros fans thanks to summer trips to the nearest Major League city (Houston) and later there came Cubs and Braves fans thanks to the advent of cable television, not to mention the requisite Yankees, Red Sox, Dodgers and Giants fans born of family tradition.

Of course baseball was a spring and summer staple at playgrounds and had a rich tradition among the high schools. Both Tulane and UNO produced top-notch college teams in the 1970s and 1980s before Skip Bertman elevated LSU to national power status with a handful of College World Series championship teams in the 1990s.

But the professional baseball fans, especially the purists alienated by the aluminum bats used by the colleges, had to wait and wait until the opportunity came to dust off their mostly-empty scorebooks, sharpen a bunch of No. 2 pencils and head back to the ballpark when the Zephyrs arrived at Privateer Park in 1993.

“There was always a niche for baseball that we thought we could fill,” said Coulon, a former minor-league player.

When the team arrived, a group of famished professional baseball fans gathered at the Home Plate Inn across the street from the former site of minor league baseball on the eve of the new team’s first game.

“New Orleans was a baseball town for a hundred years,” Fred Roberts told the Associated Press at the time. “When the old Pelicans left it broke our hearts. We’ve been waiting years for this team to get here.”

On April 16, Barrouquere arrived at the ballpark some five hours before the first pitch of the first home game against the Buffalo Bisons.

“The day couldn’t go by fast enough so I could get over there,” he said.

The Zephyrs eventually made upgrades to Privateer Park to meet the minimum requirements for Triple-A baseball, including the addition of some 4,000 seats.

“It was very beneficial to our baseball program and the university,” said Ron Maestri, the two-time UNO baseball coach who was athletic director while the Zephyrs were on the Lakefront and for whom Privateer Park was later renamed.

After two seasons at UNO, Couhig and Leger led a partnership group that bought the team from Dikeou.

“It wasn’t going to be our livelihood,” Leger said, “but we thought, it’ll be interesting, it’ll be something we can do for the community. We’ll build the stadium, it will be a legacy for us, and we’ll have fun doing it.”

With a new stadium and a long-term lease on the way, it seemed baseball was here to stay.

“Every day I just kept saying, ‘God, please let me wake up tomorrow so I can go to the ballpark,’” Barrouquere said. “I was getting paid to watch baseball. Life was good.”

But now another indefinite professional baseball drought is beginning in New Orleans.

As Yogi Berra said, “it’s déjà vu all over again.”

Movin’ On Up

Rally Raccoon never made it to Zephyr Field.

But Scott Sidwell did.

Rally was put to rest on a funeral pyre at home plate after the last professional baseball game played in Orleans Parish. He was the mascot of the Zephyrs during their final two seasons at UNO while Zephyr Field was being built in Metairie.

The financially strapped front office eagerly adopted Rally as its mascot after the moth-bitten costume was discovered in a closet even though any connection between a raccoon and the Zephyrs – either the train or the defunct roller-coaster – was spurious.

Sidwell was an intern barely a week on the job when he volunteered to bring Rally to life, climbing into the raccoon suit to greet fans around the ballpark each night.

Rally’s signature moment each night arrived during the fifth-inning “Base Chase,” a common minor-league promotion. The Raccoon would line up as a runner at first base and chase some lucky pre-teen who would get a head-start at second base in a sprint around the bases to home plate.

Rally was the Washington Generals of base chases because his official won-lost record was zero and however many base chases he participated in.

But just as the team’s mission was player development, the front office provided its own player development as young, eager interns found an entrance into their own professional careers.

Sidwell earned a full-time sales and marketing position when the franchise moved to Metairie, then landed jobs in sales and marketing with the Saints and Tulane University, became an associate athletic director at Syracuse University and the athletic director at the University of San Francisco before taking his current position as a deputy athletic director at Penn State University.

“Minor league baseball provides the essence of sports marketing,” Sidwell said. “You deal with everything from game operations, whether that’s pulling the tarp or raking the field, tearing a ticket or pouring a Coke.”

In addition to having the necessary work ethic to handle 15-hour work days, eight-game homestands, working weekends and holidays, Sidwell as Rally could walk the concourse incognito and share the fans’ experience “through the eyes of the mascot,” allowing him to relay to the staff ways to improve the customers’ experience.

“That was a great learning experience for me,” he said.

After the franchise’s stay at Privateer Park, a nice college facility but a sub-par one for Triple-A baseball, went into extra innings because of delays in passing the bill to fund the construction of the new stadium as well as longer-than-anticipated designing and construction of the ballpark, the organization and the community had grown equally impatient for the move to the suburbs.

Rally’s burning at the plate signified the end of one era as the Zephyrs moved to eastern Jefferson Parish as hopeful as were the fictional Jeffersons of the sitcom by the same name when they went “movin’ on up to the East Side.”

Out of the ashes of Rally Raccoon arose not a phoenix but a really big rat-like creature – a nutria to be more precise.

Generally speaking, a nutria is not the optimal candidate to be a minor-league baseball mascot that attracts hugs from kids.

But Boudreaux the Nutria was the perfect ambassador for minor league baseball in Jefferson Parish after a few swings and misses at mascots at UNO.

Before Rally there was a bright red crawfish. “It was really a lobster,” Leger said.

Then came “a baseball-headed thing,” Leger said. “They were all a disaster.”

When it came time to pick a mascot for the arrival in Jefferson Parish, Couhig said the local ownership group turned to their brainstorming blueprint, which consisted of bouncing ideas off of one another and determining which rose to the threshold of “won’t this be a kick in the ass.”

Boudreaux easily reached the threshold.

“You needed something uniquely indigenous to Louisiana,” Couhig said. “We knew it could be unique and fun.”

Nutria, of course, are infamous in Jefferson Parish because the gnawing they routinely do with their orange teeth has done significant damage to the parish’s drainage canals, requiring expensive repairs.

The late Jefferson Parish Sheriff Harry Lee, who Boudreaux ultimately would give a run for his money as the Parish’s most popular larger-than-life character, made national news by leading nocturnal patrols in which Lee and JPSO snipers would routinely pick off nutria to try and solve the problem.

“You heard about a giant nutria and you were like, ‘well that’s brilliant,’” Swoboda said sarcastically, “but you know what, when Boudreaux walked out there he was such a lovable figure. It was like, ‘only in New Orleans.’”

More specifically, Jefferson Parish.

The costume for Boudreaux was carefully crafted, producing a more kid-friendly chipmunk-like look – even with orange teeth – rather than an authentic nutria visage.

“He was a magnet,” Barrouquere said. “He brought out almost as many people as the games did.”

Boudreaux, who can stand a good seven feet high with a reasonably tall person inside, had popular supporting characters in his wife Clotile and a litter of baby nutria – Beauregard, Cherie, Claudette, Jean-Pierre, Noelle and Thibodaux – created to seize on the beanie baby craze of the late 1990s.

“People would line up hours before the game to get those things,” usher Tim Cronin said of the beanie babies.

It was the perfect marketing tool for a franchise marrying itself to its newfound neighborhood.

Speaking of marrying, the faux wedding of Boudreaux and Clotile, with Couhig both serving as Boudreaux’s best man and giving away Clotile and officiated by Lee himself citing “the power vested in me by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries,” drew a standing room only crowd of 11,012, bigger than any other in the stadium’s brief history, on Aug. 16, 1998.

“That might have been the hardest ticket to ever get out here,” Barrouquere said.

Even Swoboda, a baseball-first guy whose spectacular diving catch in right field in the ninth inning of Game 4 was the signature play of the New York Mets’ legendary World Series victory against the Baltimore Orioles in 1969, had to give props to the mascot.

“With all the wonderful baseball that has been played,” Swoboda said, “that in my mind was still the ultimate day at the ball yard.”

But just as the baseball team’s popularity in Metairie waned, so too did the nutria’s presence at the ball park.

The children lasted only as long as the beanie baby craze did, Clotile like an old soldier faded away and even though Boudreaux made cameo appearances for smaller and smaller crowds as part of the nightly festivities right up to the end, he struck a less-impressive figure in a more-recent, seemingly off-the-rack costume.

Thus was affirmed the enduring value of that ancient warning for conquering heroes: “All glory is fleeting.”

One Brief, Shining Moment

The name Camelot stands for any place or time of idyllic happiness.

For the Broadway musical of the same name, Frederick Loewe wrote, “Don’t let it be forgot that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot.”

The Zephyrs’ brief shining moment lasted for the first few years in the new ballpark.

“There were a lot of iconic things in the early years,” Leger said.

The baseball team certainly was in the right place at the right time when it rolled into Metairie in 1997.

Like a group of top-flight prospects maturing at the same time as the arrival of a group of veteran free agents that addressed shortcomings to form a championship-contending team, the pieces fell into place for the Zephyrs in their inaugural season in Zephyr Field.

The location of a brand new ballpark in a densely-populated, middle-income, relatively crime-free area of the city yearning for a fresh source of entertainment in the neighborhood was a heck of a starting point.

“You had a business group in Metairie that had never been tapped for something that was their own,” Couhig said.

Just being in Jefferson Parish was significant.

“One of the biggest things that I heard from a lot of people was, ‘I don’t have to venture far out,’” Cronin said, “because a lot of people considered going to New Orleans venturing far out.”

Rojas didn’t arrive until 2016, but he quickly learned that in addition to physical distance being less than it seemed, the cultural distance was greater than the proximity suggested.

“We’re just over six miles away from downtown,” Rojas said, “but it might as well be 600 miles away.”

The icing on the cake was the expiration of the player development contract with the Milwaukee Brewers, at best a middle-of-the-pack organization with no connection to New Orleans, and the opportunity to hook up with the nearby Astros.

Houston already had countless fans in the market and the parent club was building one of the better farm systems in baseball when its top affiliate landed in Jefferson Parish.

On top of ideal location came the implementation of a well-conceived marketing strategy orchestrated by general manager Jay Miller, who had overseen the final season at UNO.

“When you talk about being able to embrace a community and get them to turn out to a ball club, Jay Miller is the best I’ve ever seen. It’s hands down,” Swoboda said.

Additionally, the timing couldn’t have been better from a competition standpoint because the Saints were going through tough times.

The death of general manager Jim Finks in 1993 triggered the end of the franchise’s most successful run to that point and ultimately the end of Jim Mora’s 11-year stretch of unprecedented success as head coach in 1996.

Owner Tom Benson was being vilified for seemingly bilking hundreds of millions of dollars from the state through not-so-thinly-veiled threats to move the franchise even as ticket prices continued to soar and playoff appearances vanished.

Then the ill-conceived hiring of Mike Ditka to succeed Mora brought on a moribund three-year stretch that coincided with the arrival of the Zephyrs, their long-term lease with no threats of relocation, fan-friendly ticket prices and a Midas marketing touch compared to Benson’s ham-handedness.

“They were struggling both on the field and public-relations wise,” Leger said of the Saints.

The relationship between the two franchises was strained by the fact that Benson had purchased the rights to the name “Pelicans” and planned affix it to the Double-A Charlotte Knights that he would purchase and move to UNO.

But he got trumped by Dikeou and Couhig having Triple-A rights, denying what Couhig called Benson’s desire to be “czar of all sports.”

Benson sued, but Dikeou and Couhig prevailed with the rights to the market while Benson held on to the Pelicans name, which came in handy when he bought an NBA team later on.

After the dispute was settled, Couhig said, “I made a decision when I walked out of there, we’re going to show people how to do it right.

“And we did and we never missed a chance to draw a comparison (to the Saints) without ever saying it.”

In fact, much of the baseball team’s early success stemmed from being different than the Saints – the convenience, affordability and safety of playing in the suburbs, being family oriented, bringing the city its first national team championship, then lowering some ticket prices when demand was at its highest.

“It was an easy contrast,” Couhig said.

Triple-A baseball was no substitute for the NFL, but some fans questioning the value they were getting for the high-priced Saints tickets found better value for their entertainment dollar and the Zephyrs found their niche.

Airline Highway Revisited

U.S. Highway 61 stretches practically the length of the country, spanning some 1,400 miles from Minnesota near the Canadian border into New Orleans.

The highway essentially hugs the Mississippi River, passing through Memphis and the Mississippi Delta – Blues country.

Its northernmost stretch begins near Bob Dylan’s hometown of Duluth and the road was the inspiration for Dylan’s landmark album – “Highway 61 Revisited” – serving as a path into the Blues phase of his career.

“Highway 61 begins about where I came from,” Dylan wrote in his memoir “Chronicles Volume One. “I always felt like I’d started on it, always had been on it, and could go anywhere from it.”

The southernmost end of Highway 61, though, held far less promise.

Legend has it that the portion from Baton Rouge to New Orleans was commissioned by Governor Huey P. Long nearly 90 years ago to shave some 40 miles off his regular trips from the Governor’s Mansion to his favorite bars and restaurants in the French Quarter.

Airline Highway, as that stretch was known, featured bar rooms, discount motels and run-down businesses throughout the connection between Louisiana’s capital city and its bawdiest city.

Well after Long’s assassination in 1935, Airline Highway’s notoriety mostly came from nefarious persons, places and events.

The Town and Country Motel on Airline Highway in the heart of Metairie served as headquarters for Carlos Marcello, the self-proclaimed “tomato salesman,” presumed Mafia boss and in some minds the prime suspect as mastermind of the assassination of President Kennedy.

Marcello’s office was an anomaly as most motels on Airline Highway rented space on a far less permanent basis.

The road’s reputation as a poor man’s Bourbon Street was reinforced in 1987 when television evangelist Jimmy Swaggart was caught leaving another Airline Highway motel with a prostitute, a mere four miles east of Marcello’s former headquarters.

“If you looked at the footprint all along Airline Highway,” Maestri said, “it wasn’t a pretty footprint.”

The 18-mile stretch that serves as a well-traveled entrance to New Orleans from Louis Armstrong International Airport was a blight on a metropolitan area anxious to demonstrate that it had more to offer visitors and locals than just the seamier parts of the French Quarter.

Then came Zephyr Field.

Its construction coincided with the renaming to Airline Drive the stretch of Highway 61 that spans Jefferson Parish as part of the revitalization of the area where the baseball stadium would be built and ancillary projects would follow.

Airline Drive won’t be confused with the Champs-Elysees, and it isn’t lacking in bar rooms or motels these days, but even those establishments have generally been upgraded amid the overall sprucing up of the area surrounding the baseball stadium.

“This whole place has really cleaned itself up,” Maestri said.

If Gov. Long were still around, there’s little doubt his motorcade would zip past the daiquiri shop near the stadium in search of more traditional taverns and anyone in search of discount, by-the-hour rooming would have to venture a bit from the ballpark to do so.

Leger said parish leaders “wisely” saw the construction of the baseball stadium “as an anchor on a different scale but in a similar way to how the Superdome was an anchor to Poydras Street and transformed Poydras.”

“The transition from Airline Highway to Airline Drive was startling to watch,” Swoboda said.

The stadium eventually underwent a name change of its own.

The change of the team’s nickname from Zephyrs to Baby Cakes for the 2017 season (more on that later) required that the stadium be called something other than Zephyr Field and no one was going for Baby Cakes Field.

The stadium name was unofficially changed to “The Shrine on Airline,” a nickname given to the building by the team’s first public address announcer, Derrick Grubbs, when Zephyr Field opened.

The stadium was a nice $20 million state-funded project that became a “shrine” when the local owners decided to pump in a few million dollars of their own money to upgrade it.

They read that a swimming pool was being planned for the Arizona Diamondbacks’ new stadium and they beat them to the punch by adding a pool and two hot tubs beyond the right-field wall.

Then they planned a berm in center field that would naturally be called “The Levee.”

They discovered that the original plans called for The Levee to be 10 feet lower than Monkey Hill, the spot in Audubon Zoo generally accepted as the highest point in South Louisiana.

Once they realized how close they were to eclipsing Monkey Hill, Leger said, “we had another drink and said, ‘let’s go.’”

The stadium quickly became more than the home to a minor-league team.

The stadium was the site of high school state championships and most recently LSU’s annual Wally Pontiff Jr. Classic, named in honor of the late Tigers star that grew up in Metairie.

LSU and Tulane played before record crowds in an historic NCAA super regional in 2000 as the Green Wave’s best team ever beat Bertman’s final Tigers team for a spot in the College World Series.

The stadium was the site of the 1999 Triple-A All-Star Game, which set the tone for liberal expansion of the venue’s resume’ for big events.

Minor-league soccer had modest success and non-sporting events were held in the stadium as well.

It was the site of a Presidential address by George W. Bush in April of 2001 and less than six months later a vigil in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The shrine routinely hosted post-game concerts and was even turned into a haunted house leading up to Halloween for a couple of falls.

So all types of people were drawn to the stadium for a variety of events.

“This is the entertainment focal point for Jefferson Parish,” Maestri said.

Eventually softball and soccer fields were built in LaSalle Park on the west side of the stadium, later adjoined by the Jefferson Performing Arts Center and Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office sub-station.

“It was certainly a catalyst for some newer development,” Coulon said. “The beautification of that area has enhanced that corridor over a period of years.”

The Baseball Gods Are a Fickle Lot

Baseball is a quirky game.

The hardest-hit line drive can turn into the most routine of outs and the softest pop fly can become the least playable of base hits.

In fact, baseball success sometimes is the result of merely being in the right place at the right time and failure sometimes is the result of merely being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Some attribute it to the fickleness of the “baseball gods” and there appeared to be some sort of divine intervention after the arrival of the Zephyrs and certainly an absence of it leading up to the departure of the Baby Cakes.

The idea for the baseball stadium emerged when a handful of Jefferson Parish elected officials decided in the early 1990s that tax dollars would be well spent on a minor-league park after it became clear that Major League Baseball was never coming to the Superdome.

Couhig traveled to Baton Rouge to lobby for a bill to fund the project.

“We got it through the House,” he recalled.

Then it went to the Senate.

“It was the last bill on the last day and it didn’t pass,” Couhig said. “It didn’t get voted down, but it died when the session adjourned.”

Couhig wondered, “What the heck just happened?”

A senator from the New Orleans delegation explained.

“It’s a great bill,” Couhig recalled with a chuckle. “It just needs a little fine tuning.”

It was finely tuned all right – and expanded tenfold into a $200 million bill that included among other things the renovation of the Louisiana Superdome, the much-needed construction of a new training facility for the Saints, a multi-purpose arena in Westwego as well as recreational facilities in multiple parishes.

But the centerpiece of House Bill No. 2013 was the construction of an arena next door to the Superdome with the goal of luring an NBA franchise.

“There was a common cause for Jefferson and Orleans to want to participate in that,” Coulon said.

The new bill easily passed the Legislature and Gov. Edwin Edwards signed it into law in the summer of 1993, during the baseball team’s first season at UNO.

“Everybody was a winner,” Maestri said.

But the project wound up being an example of how unintended consequences can arise.

The New Orleans Arena (later renamed the Smoothie King Center) lured the Hornets NBA franchise (later renamed the Pelicans after Benson bought the team and finally got his money’s worth out of the nickname) from Charlotte, N.C., for the 2002-03 season, which helped initiate the baseball team’s ultimate demise.

The NBA gave preliminary approval of the relocation, provided New Orleans could meet ambitious benchmarks in sales of tickets, suites and sponsorships. Government and business leaders went into a full-court press with potential sponsors and ticket buyers and met each benchmark, gaining easy approval from the league owners.

The arrival of a second major-league franchise immediately ran the minor-league hockey team known as the Brass out of town.

It also meant an inevitable exodus of sponsors and season-ticket holders to the new franchise in town, signaling that the Zephyrs were beginning a slow decent from their peak like the post-prime of a pitcher can be foretold by a fastball registering a couple of miles per hour slower on a radar gun.

“We knew that someday a basketball team was going to impact us dramatically and I think it unequivocally did,” Leger said. “You could immediately feel the air sucking out of the advertising dollar when the Hornets came here.”

The bill that made minor league baseball viable in Metairie also attracted competition that would gradually chip away at its viability.

“Obviously everybody is after the same dollar,” Maestri said.

Zephyrs radio play-by-play announcer Tim Grubbs arrived in New Orleans several months before the NBA team.

“Broadcasting games here, it was electric,” Grubbs said. “But when the Hornets came I saw a little bit of a drop-off and then over time it was even more of a drop-off.”

Even after 56 games, Joe DiMaggio couldn’t keep getting a hit every day and the Zephyrs’ run also came to an end.

“In 1997 you had a coalescence of all kinds of good, positive things, but you know what?” Swoboda said. “Time moves on and those things don’t all last.”

Just as age turned the stadium from an asset to a liability, so too did other factors change from being helpful to harmful during the baseball team’s tenure.

Couhig brought in North Carolina businessman and well-respected minor-league owner Don Beaver as a partner in 2001, then Beaver bought out Couhig the following year.

“I thought I had gotten it as good as I could get it,” Couhig said of the franchise.

Miller left his post as GM during the ’98 season to become general manager of a new Double-A franchise in Round Rock, Texas, a suburb of Austin.

Round Rock would later become the Astros’ Triple-A affiliate and Houston severed ties with the Zephyrs in 2005.

Then came Hurricane Katrina.

The baseball team was the only New Orleans franchise not to be displaced by the hurricane, but it was a landmark moment in the franchise’s slide nonetheless.

The football team spent the 2005 season in San Antonio and the basketball team spent the 2005-06 and 2006-07 seasons in Oklahoma City.

The Zephyrs lost a total of three games to the storm, which hit during the final homestand of the 2005 season, and the 2006 opener drew a record crowd as the baseball team was the first to play a full season back home after Katrina.

But things have gone downhill ever since.

When the Saints returned early in 2006, Benson seemed to find a Midas touch of his own.

The hiring of Sean Payton as coach, the signing of free-agent quarterback Drew Brees and a whirlwind of talent acquisition turned the on-field product around nearly 180 degrees.

Meanwhile, Benson adjusted to the economic realities of the post-Katrina market, lowered ticket prices and the team sold out on season tickets for the first time, something that has continued ever since.

Along the way, the Saints won a championship of their own, prevailing in the Super Bowl after the 2009 season.

“The Saints have vastly improved in all areas,” Leger said.

In post-Katrina New Orleans, everyone else that is competing for the entertainment dollar has had to contend with what Swoboda called, “The 8,000-pound gorilla that is the Saints.”

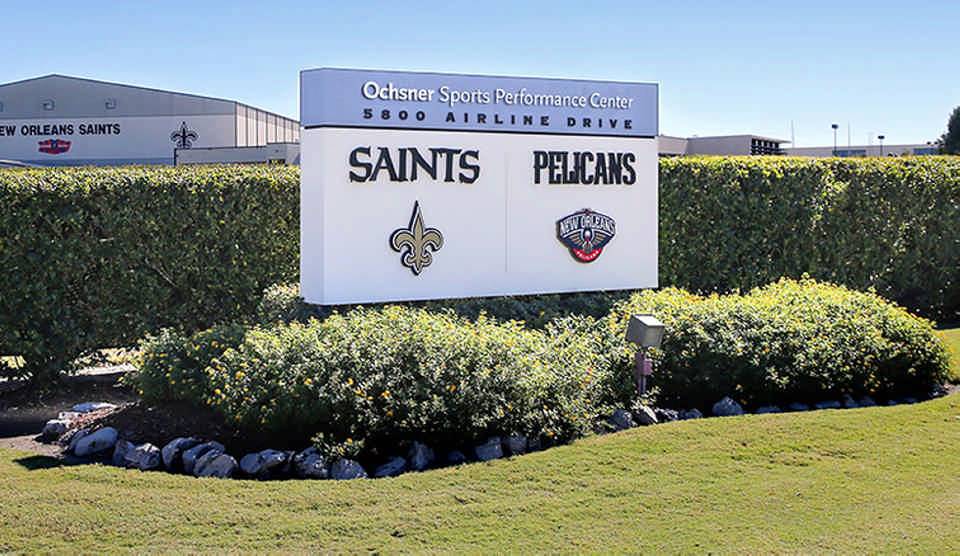

The Saints’ emergence as one of the model franchises in the NFL since 2006 and the arrival of the NBA have helped squeeze the Baby Cakes out of the market, a development symbolized by the two major-league franchises’ first-class joint headquarters looming over the aging baseball stadium next door.

Benson died at age 90 in March of 2018 and ownership of the Saints and Pelicans passed to his wife Gayle, who has astutely overseen continued success by both franchises.

The Saints are coming off their first set of back-to-back division titles and narrowly missed the Super Bowl after a controversial overtime loss in the NFC Championship last season.

The Pelicans finished a disappointing 33-49 last season after star forward Anthony Davis rocked the franchise with a mid-season trade demand that loomed into the off-season.

But Mrs. Benson’s commitment to bringing her basketball team up to par with her football team has produced a rejuvenating offseason. She hired widely-heralded David Griffin to run the basketball operation, then pledged significant upgrades to staffing and facilities, which Griffin seems to be taking full advantage of.

Then came perhaps a little divine intervention for the baseball team’s neighbors as the Pelicans overcame long odds to win the draft lottery and select Duke forward Zion Williamson, who many observers have lauded as a one-in-a-generation talent.

That started a remarkable roster overhaul comparable to the Saints’ in 2006, producing a new-found zeal for New Orleans’ NBA franchise.

Even the baseball team’s seemingly ideal locale had a flip side to it.

“Jefferson Parish has changed since Katrina,” Grubbs said.

Studies show that the population of Jefferson Parish is less than it was pre-Katrina and a higher percentage of households are “empty nests,” meaning a smaller percentage of the residents are young families compared to when the initial attendance surge took place.

Additionally, the sense of ownership that Metairie feels toward the franchise never extended to a significant degree beyond the 17th Street Canal, the South Shore of Lake Pontchartrain or the western edge of Highway 61, where it’s still known as Airline Highway.

“I hate it,” Grubbs said, “but I think one of the reasons why this doesn’t work is that this is Metairie’s team. So people from Uptown or the West Bank or the Warehouse District don’t feel like they need to come. They feel like, ‘oh, that’s Metairie’s team.’

“With the Saints it doesn’t matter if you live on the North Shore or the West Bank or Uptown or Kenner, we all root for the Saints.”

The match-made-in-heaven partnership with the Astros is a distant memory as the closest Major League franchise is less than two years removed from its first World Series championship and is still one of the elite franchises in the big leagues.

While the Astros’ Triple-A franchise continues to thrive in Round Rock, the Baby Cakes have labored under the flag of the struggling Miami Marlins for the past 11 seasons.

“We haven’t been blessed here with a good affiliate,” said Maestri, who served as the Zephyrs’ COO from 2005-14.

Some 22 years after the Shrine on Airline opened it’s being replaced as the soon-to-be-renamed-again team’s home by a $75 million state-of-the-art facility set to open in Wichita next March like a fading veteran ballplayer being supplanted by a young, elite prospect.

And in one last bit of irony, Miller, whose image is enshrined in the New Orleans Professional Baseball Hall of Fame inside the Shrine, has been hired by Baby Cakes owner Lou Schwechheimer, who bought the team from Beaver in 2015, to spearhead the move into the new stadium in Wichita just as he shepherded the franchise’s move from UNO to Metairie.

It’s hard to imagine a more challenging set of circumstances for a minor-league baseball team to encounter than those that helped run the Baby Cakes out of town, just as it would be difficult to imagine a more helpful set of circumstances than the one that greeted the franchise at the parish line in the late 1990s.

The baseball gods are indeed a fickle lot.

“A Childhood Memory Gone”

Shoeless Joe Jackson played the final seasons of his baseball career under an assumed named as he bounced around semi-pro leagues after being banished from the Major Leagues for his role in the Black Sox Scandal in which he and several Chicago White Sox teammates threw the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds.

Similarly, New Orleans’ baseball team operated for its final three seasons under what many considered an assumed name.

In 2016, Rojas said, the organization and the brand “needed a pick-me-up,” so it held a contest to rename the team.

Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any name would smell as sweet,” but changing the name of New Orleans’ baseball team proved to be a thorny matter.

Barrouquere was part of a committee of locals that had input into the new name in the same sense that a catcher has input into whether a pitcher determined to shake him off until he sees what he wants ultimately throws a fastball or a breaking ball.

“We told them, don’t get cute. People won’t go for it if you try to come up with some of this cutesy stuff,” Barrouquere said. “But they didn’t listen.”

The front office, guided by a consulting group from California, chose “Baby Cakes” to be the team’s new nickname even though locals had no idea what it meant.

“Is a baby cake the baby in a king cake?” Leger asked. “If it is, that would be a cake baby.”

Couhig, who called the name change “the worst thing ever,” said the name selection prompted him to compose the only letter to the editor he has ever written.

“It was because it was such a stupid, stupid idea,” Couhig said. “It was an embarrassment to the city.”

Couhig began his letter to the Times-Picayune thusly, “What the heck is a Baby Cake? Nobody knows. Not us locals at least. The out of town marketing firm that helped the out of town owners of our AAA baseball team rename the Zephyrs might think they are talking about a king cake baby. But those of us who actually eat king cake know better.”

Barrouquere said people who knew he was part of the committee started to send him emails, texts and call him as well as stopping him at church, asking, ‘What the hell were ya’ll thinking?’”

Barrouquere said people who knew he was part of the committee started to send him emails, texts and call him as well as stopping him at church, asking, ‘What the hell were ya’ll thinking?’”

He attended the news conference at the stadium to announce the new name.

“When they said Baby Cakes,” Barrouquere recalled, “I walked out and said, ‘that’s it.’”

He didn’t set foot in the stadium for nearly three years.

Barrouquere stopped using the season tickets he had been buying since retiring from the newspaper, though he kept buying them even as friends similarly upset by the name change canceled their tickets.

“I wasn’t going to turn my back on them; I wanted to support baseball,” Barrouquere said. “But I cannot with a straight face go out there and root on Baby Cakes. I thought it was ridiculous.”

Though the forced moniker with no authentic connection to New Orleans was considered a strikeout by many locals, it was a marketing success, not really a home run but at least a stand-up double.

The accompanying logo of, in Rojas’ words, “not an angry baby, but a determined baby that shows the spirit of the people of New Orleans that overcame Hurricane Katrina” spurred a huge boost in merchandise sales.

But ticket and sponsorship sales remained another matter entirely.

“A night at Zephyr field was synonymous with fun,” Couhig recalled in his letter to the editor. “Games were a must on every family and company checklist. We were among the top in the country in attendance, won the city’s first world championship in a professional sport, and everyone had fun doing it. That’s the New Orleans way.”

Though the franchise already was fading from the public’s consciousness before the name change, in the minds of many locals the adoption of the Baby Cakes’ name was the final nail in the coffin.

Clearly the franchise that had thrived under local ownership was no longer New Orleans’ team in the way that it once was.

Gradually the inevitably of the franchise’s demise became clearer, then public knowledge shortly after the end of the 2018 season, leading to a lame-duck final season.

The organization continued to go through the motions with the familiar promotions and themes until the end.

On a “Fireworks Friday” night in mid-May, the parking lot of the Winn-Dixie across the street from the baseball park was half full.

Nearly all of the cars were located near the entrance to the grocery, but a handful were askew at the end farthest from the store.

As had been the tradition since the stadium opened, as soon as the Friday game ended, the sky would light up like the Fourth of July.

In the early days of the stadium, the parking lot would fill up and dozens of cars would spill onto the shoulder of Airline Drive. Neighborhood residents who didn’t have the time, money or inclination to buy a ticket and sit through the game would await the game’s end and watch the fireworks from their cars.

On this night Beaux and Lacy Caro are seated inside their vehicle, watching the fireworks, just as they have done each baseball season since the stadium opened, long before they met, got married and bought a house a few blocks away.

They didn’t buy the house because of its proximity to the stadium, but, Lacy said, “It was a perk.”

Her parents divorced when she was three years old and she went to live with her mother in Des Moines, Iowa, while her father remained in Metairie.

Lacy would see her father only when she was on vacation from school, primarily in the summer. They would go to a couple of games a month during the heart of baseball season.

“The draw was the fireworks,” Lacy said, “but my dad also taught me about baseball by watching the Zephyrs.

“That was a way for a little girl to relate to a single dad who had only a little girl. It was something we could connect on. Baseball is very dear to my dad. It’s a very special memory that I hold with my father.”

The last fireworks show was Thursday.

“It’s a childhood memory gone,” Beaux said.

“I’m Probably Not Going To Get a Chance To See This Again”

In the movie “Bull Durham” Crash Davis was an aging catcher signed by the Durham Bulls’ parent club for one reason – to be a mentor who would prepare exceptional prospect Nuke LaLoosh to pitch and survive in the Major Leagues.

For most of a season Davis dutifully endured and educated the youngster who was both unusually gifted and unusually immature.

As the end of summer approached, LaLoosh got the inevitable call-up to “The Show” and Davis, having outlived his usefulness, got his release. He eventually landed with the Asheville Tourists and late in the season – in virtual anonymity – broke the minor-league record for career home runs when he hit No. 247.

Annie Savoy, Davis’ on-again, off-again love interest, noted that the feat went largely unnoticed.

“When Crash hit his 247th home run, I knew the moment it happened,” she said. “But I’m sure nobody else did. And The Sportin’ News didn’t say anything about it.”

New Orleans’ franchise sent countless real-life versions of Nuke LaLoosh to the major leagues as they became Brewers and Astros, Nationals, Mets and Marlins.

But the team, like Crash Davis, seemed to outlive its usefulness and played its final days in virtual anonymity.

New Orleans, which hasn’t ranked higher than 10th in the PCL in attendance since the NBA’s arrival, finished last each of the final two seasons. This season it drew an announced average of fewer than 3,000 fans but often played in front of much smaller crowds.

At the first game of the final homestand, Gary Baylor sat by himself at the top of Section 223 in the upper deck on the first-base side.

He had been to the stadium “maybe once or twice” before this season because his job conflicted with the games. But now semi-retired, he came out in the middle of this season.

“I’ve only missed one or two games since then,” he said. “It’s been a lot of fun.”

Baylor started counting the crowd on particularly sparse nights.

“The lowest was 29 people,” he said.

The final season was almost like the Jazz funerals for which New Orleans is known.

There might as well have been a dirge playing in the early going as each home game felt like an obligatory sad march to say goodbye.

Though the mourners never exactly broke into a Second Line, at some point after the All-Star Break the mood did seem to become less somber and if not exactly celebratory at least nostalgic.

George Carlin famously riffed on the contrast between football and baseball, noting football’s closeness to a military exercise in war-like conditions while “in baseball the object is to go home! I’m going home.”

Gradually a lot of folks came home to the Shrine as the final season wound down, some seeking closure, some just to say goodbye, others reliving memories like Old Timers Day at Yankee Stadium.

And there were lots of memories – sellouts, Fourth of July fireworks shows, cameo appearances by future major leaguers such as Troy Glaus, Kris Bryant and Mark Prior.

There were two no-hitters thrown by Zephyrs – Scott Taylor’s at UNO in 1994 and Brian Powell’s at Zephyr Field in 2001.

There was Zephyrs first baseman Daryle Ward being named the Most Valuable Player in the 1999 Triple-A All-Star Game.

There were playoff appearances in 1994, 1997, 1998, 2001 and 2007.

New Orleans shared the 2001 PCL title with Tacoma when the championship series was canceled in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

But it was that ‘98 championship in the Triple-A World Series, an event that lasted just four seasons, that still stands out the most.

The rain-shortened first-round playoff series against Iowa was tied at one game apiece as the final day for a deciding game to be played arrived at Zephyr Field with the start of the PCL championship series looming in Calgary. If the game wouldn’t be played, the Cubs would advance by virtue of a better regular-season record.

The game was scheduled for mid-day, which is when days-long rains from Tropical Storm Frances finally abated, leaving a small window to prepare a field that was completely under water.

“Every minute counted,” Leger said.

Just a few weeks earlier, one of Leger’s sons had played for the St. Bernard Parish team in the Dixie Boys World Series in Houma, where a similar challenge was presented.

Locals brought two air boats on to the field to blow the standing water off the field to help get the diamond playable.

Leger wondered aloud if there were any nearby airboats that could be enlisted when general manager Dan Hanrahan remembered, “We have a season-ticket holder that owns a helicopter.”

Panther Helicopters came to the rescue with a chopper that flew into the stadium and hovered over the field for much of the afternoon as the whirring blades dispersed the standing water.

“To me that was the miracle of that season,” Leger said, “that helicopter drying the field.”

After the helicopter had started the salvaging of the field, the grounds crew came out of the bullpen and finished up the day-long clean-up.

“We started at the last possible moment,” Leger said.

The Zephyrs prevailed 2-1 and were off to Calgary, where they won three games to two. Then it was off to Las Vegas, where New Orleans defeated Buffalo 3-1, clinching the title as Hurricane Georges was bearing down on the Crescent City.

Leger, who had always been a nightly fixture at the ballpark, skipped opening night this season for the first time that he could remember. It turned out he didn’t miss anything as the opener was rained out.

He was slow to return, but did turn out for a few games in late August, including the finale.

A few dozen former employees took over one of the suites for a reunion in early August.

Couhig said he had attended just one game since selling to Beaver in 2002 before popping in during the second-to-last home-stand.

“I have a philosophy,” Couhig said. “When you own something and you sell it, it’s never going to be as good as you thought you were doing and it’s not going to be as bad as you think they’re doing. I wanted to be fair to Don Beaver and his management group.

“It’s better to cut the cord and move on.”

Even Barrouquere dropped his protest of the name change and started showing up periodically “because I’m probably not going to get a chance to see this again in my lifetime.”

The in-stadium gift shop continued to sell Zephyrs and Pelicans merchandise alongside Baby Cakes stuff through the final home game. On the final night the gift shop looked like a toy store at closing time on Christmas Eve as last-minute shoppers gathered up final souvenirs and gifts.

It would have taken Baylor much of the night to count the final crowd, but the stadium was still more than half empty.

The Saints were playing their preseason finale in the Superdome while Tulane was playing its season opener uptown.

The anticipation was high for both football teams as the Saints are generally considered Super Bowl contenders again and the Green Wave are coming off a bowl victory for just the fifth time in school history.

On top of that, it was the 14th anniversary of the day Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans and the Gulf Coast. That didn’t necessarily have a direct impact on the attendance for the finale, but it was yet another item to distract locals from the baseball team’s departure.

The last ceremonial first pitches were thrown by representatives of the Jefferson Parish Recreation Department’s East Bank Little League World Series softball and baseball teams.

The girls team finished as runners-up in mid-August before the boys, who are based a mere four miles from the Shrine in River Ridge, delivered Louisiana’s first Little League World Series national championship, followed by a world championship four days before the Baby Cakes’ finale.

Those dual feats capped an unprecedented summer of success for local amateur baseball.

The New Orleans Boosters won the All-American World Series championship and the Pedal Valves American Legion team reached the semifinals of its national tournament.

“(Triple-A baseball) was good for college baseball, it was good for high school baseball, it was good for youth baseball,” Maestri said. “Kids could see baseball at a high level. You had the next-best thing to Major League Baseball here.”

The first pitch of the Baby Cakes’ last home game was hit by Memphis’ Randy Arozarena for a home run.

New Orleans tied the score in the second before taking a 5-1 lead in the fourth. But The Redbirds would hit five home runs, tying the score in the sixth and taking an 8-5 lead in the ninth.

The Baby Cakes’ first two batters in the bottom half singled, bringing the tying run to the plate.

But the opportunity to create one final lasting memory dissipated as the next three batters all struck out swinging, dashing the crowd’s hope like the hero in Casey at the Bat.

A few minutes later came a brief, perfunctory fireworks show and that was that.

Folks scattered in various directions and the Shrine on Airline went dark.

They Built It and People Came, but …

And now it’s Labor Day – the symbolic end of summer and the traditional final day of the Pacific Coast League baseball season.

But more significantly this is the 125th anniversary of the holiday created to celebrate the contributions and achievements of American workers.

The baseball team’s presence brought myriad job opportunities – for concessionaires, sign makers, IT specialists, cleaning crews, exterminators, food vendors, office supplies, bus companies, hotels, airlines, car and truck rentals, and promotional items manufacturers among others.

It also provided lots of opportunities for gameday workers – an average of 50-100 gameday employees (depending on the size of the crowd) for an average of 72 home games per season: college students and recent graduates thirsting for valuable experience, baseball aficionados seeking a closeness to their favorite game, day workers seeking to supplement their income, retirees trying to stay busy.

Tim Cronin was a utility infielder among the gameday employees.

He worked on the Zephyrs ground crew the first year in the new stadium, later worked as an usher, director of clubhouse operations, and was promoted to overseeing the gameday staff.

After a four-year hiatus during which he was establishing his own business, Cronin, who still has his staff shirt from the first season in Metairie 1997, returned this season as an usher.

“Being here the first season made me want to be here for the last season,” he said.

Tom Ninestine is a native of Geneva, New York, who moved to Metairie three years ago from Pensacola, Florida, where he and his wife, Amy Mosberger, used to attend the Double-A Wahoos Game. They met in 1991 in Geneva at a Single-A game featuring the Cubs’ affiliate.

He quickly found a home at the Shrine as an usher.

“I live about 15 minutes from here,” Ninestine said. “I thought, what better way to meet people and get to know a little about the area than to come to the baseball game?”

Tony Avallone had his 68th birthday the day before he would work his final game as a Baby Cakes usher in the home finale.

He worked offshore for 38 years for BP before retiring four years ago and setting his sights on a job at the stadium. He first applied in May but the organization was fully staffed.

“The next season I bugged the heck out of them until they did hire me (for the 2016 season),” said Avallone, who eventually found a home on the third-base side where the visiting team and its followers provided a variety of new acquaintances for him.

“That’s what it’s all about for me – meeting new people and I get to watch baseball for free, which is one of my passions,” Avallone said. “I have fans that return year after year and say hello to me and we have nice conversations. It’s almost like a small family.”

Avallone has made friends with visitors from all over, including Great Britain, Germany and Austria.

The family of four from Austria came to the Shrine two years ago, two days after witnessing a baseball game for the first time when they passed through Houston on their way to New Orleans.

“I sat with them pretty much during the whole game and explained all the nuances of it,” Avallone said. “I made sure they got a baseball. I made sure they got beads when they were being thrown. I took good care of them and that developed a friendship.”

The family is back in the U.S. on another vacation, keeping in touch with Avallone via Facebook Messenger as they travel the area where he group up in Thousand Islands, N.Y.

“They’re sending me pictures of what they’re doing and we’re talking back and forth,” Avallone said. “It’s an exciting thing to develop a relationship with somebody that’s from another country.

“This is my fun job. I would do this for free.”

He pretty much did because he and his wife live in Covington and his one-hour commute each way essentially guzzled his minimum-wage salary.

“I’m not doing this for the money,” Avallone said. “I’m doing it for the love of the game.”

Avallone stood behind home plate on the concourse after the final home game. He had been through season finales before.

“But this is the end of an era now,” he said.

The New Orleans Gold professional rugby team has talked to the Louisiana Stadium and Exposition District – the stadium’s landlord – about possibly playing their home games in the Shrine next season, but that’s a mere eight events.

Perhaps minor league soccer will return and high school football games could take another crack at it at some point.

But no one knows when or even if it the Shrine will again be lit and its gates will be opened for a professional baseball game.

Meanwhile, life goes on in the neighborhood.

Next door, walkers, joggers, soccer and softball players, as well as patrons of the arts, won’t miss a beat. On the other side of Airline Drive (not Highway) people are making groceries at the Winn-Dixie, folks are picking up fast food at a variety of restaurants and the Harley-Davidson store, a couple of banks, a few bars and dozens of other establishments will go about their business as always.

Meanwhile, some 700 miles away in Oklahoma City, New Orleans’ Triple-A franchise has played its final game – a 10-1 victory against the Dodgers.

It has been 317 months since professional baseball returned to New Orleans.

It is game number 3,834 since 1993, number 3,182 since the Shrine on Airline opened. The team won 1,860 and lost 1,974 while representing New Orleans, falling just short of 1,000 victories in the Crescent City with 978, compared to 924 home losses.

It is game number 3,834 since 1993, number 3,182 since the Shrine on Airline opened. The team won 1,860 and lost 1,974 while representing New Orleans, falling just short of 1,000 victories in the Crescent City with 978, compared to 924 home losses.

This year’s team was pretty good, staying competitive in a very challenging American Southern division of the PCL before fading from playoff contention not long after the All-Star Break.

It finished 73-65, good enough for just third place in the four-team division but sixth best in the 16-team league, its highest winning percentage (.529) since 2001.

More than 1,000 players, managers and coaches called New Orleans home at some point during the last 27 years just because the city had a professional baseball team.

After the mascots and fireworks, the job opportunities, economic development and buildings that testify to the fact that something important was once here, this story ends as it began – with baseball.

Next spring, some 160 communities in the U.S. will hear the call of “Play Ball!” once again, but for the first time in nearly three decades, New Orleans won’t be in that number.

“I’m going to be sad,” Swoboda said. “There will be a big vacancy in my program come next spring when the team is not coming out of spring training.”

Swoboda said he might have to make a road trip next season to catch up with Grubbs, who will continue as the team’s radio voice in Wichita, in order “to get my baseball fix.”

Grubbs already has settled his family into their new home in Wichita and he’ll be joining them any day.

“I’m excited about the new ballpark,” he said, “but I’m going to miss this place. I hope it’s not the end.”

Autumn is looming, but back on the first day of summer, Peter Barrouquere sat in the press box from which he covered hundreds of games at the Shrine.

This time he was on the receiving end of the questions as he reflected on professional baseball leaving his hometown – again.

He said he has a cable package that enables him to watch any Major League game on TV.

“But,” he started to say before turning his head toward the field where the Baby Cakes and the Nashville Sounds were getting under way.

Then as if on cue Sounds leadoff hitter Zack Granite hit a sharp one-hopper that seemed headed for right field. New Orleans first baseman Yangervis Solarte dove to his right, snared the ball with his glove, turned and from his knees tossed a strike to pitcher Joe Gunkel for a major league-quality out.

“But,” Barrouquere repeated, “it’s not the same as coming out and watching that.”

The conversation inevitably turned to those childhood years with the baseball Pelicans.

“Every year it seemed like an eternity before the season started again,” Barrouquere said, “and I guess that’s what it’s going to be like now.”

Somewhere in the back of his mind was lurking the memory of that ill-fated drive to Tulane and Carrollton nearly 60 years earlier.

Barrouquere paused for a moment to get a better grip on his swelling emotions like a batter nudging his fingers up the shaft of a bat to prepare for a two-strike pitch.

“I will miss the hell out of this.”

In the movie “Field of Dreams,” Ray Kinsella was working in the cornfield on his Iowa farm as a mysterious voice whispered to him, “If you build it, he will come.”

The voice repeated itself until Kinsella peered into the distance and saw a vision of a pristine baseball field that would change his life once he built it.

A few Jefferson Parish leaders had a similar vision nearly 30 years ago as they surveyed the wooded area of Metairie known as the LaSalle Tract and pondered the possibilities.

Then they teamed with the state Legislature and Couhig’s ownership group to build Zephyr Field.

And people came; they most definitely came.

But if you listen closely the voice in that cornfield never said anything about sticking around.

- < PREV Joe Burrow earns offensive player of the week honors from SEC, Louisiana sportswriters

- NEXT > Amberly Waits rewrote school softball’s record book to reach LA Tech Hall of Fame

Les East

CCS/SDS/Field Level Media

Les East is a nationally renowned freelance journalist. The New Orleans area native’s blog on SportsNOLA.com was named “Best Sports Blog” in 2016 by the Press Club of New Orleans. For 2013 he was named top sports columnist in the United States by the Society of Professional Journalists. He has since become a valued contributor for CCS. The Jesuit High…