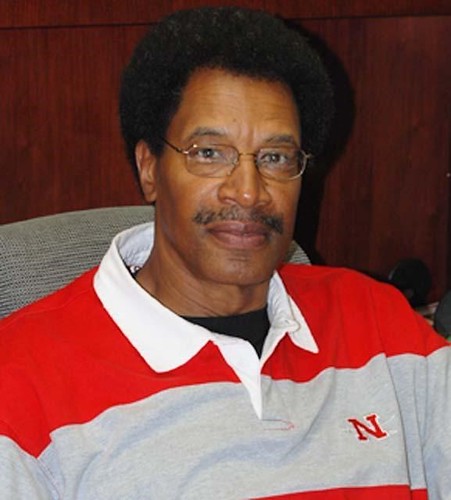

History-making college professor Cleveland Hill earns Louisiana Basketball’s top honor

By: Christina Hill

Written for the LABC

THIBODAUX, LA – In the movie, Black Panther, King T’Challa, a warrior-turned-monarch and academician who holds a doctorate degree, rules his land of Wakanda with compassion and emotional intelligence.

THIBODAUX, LA – In the movie, Black Panther, King T’Challa, a warrior-turned-monarch and academician who holds a doctorate degree, rules his land of Wakanda with compassion and emotional intelligence.

For some, Black Panther was their first introduction to a Black super hero – to a poised and quietly courageous man whose greatest assets were logic and reasoning rather than brute strength. For my sister and me, we grew up with this man at home, our very own super hero and dad, Cleveland “Cleve” Hill.

On May 5, 2018, Hill will be named 2018 Mr. Louisiana Basketball, the highest honor bestowed annually by the Louisiana Association of Basketball Coaches (LABC). He will receive the award during the LABC’s 44th Annual Awards Banquet at the Embassy Suites Hotel in Baton Rouge. The banquet is sponsored by the Baton Rouge Orthopaedic Clinic.

The state’s college basketball coaches bestow the annual award upon someone “who has made a significant, long-term contribution to the game of basketball at any level in the state of Louisiana.”

A basketball standout at Nicholls State University in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Hill is a super hero, not just for his athleticism but for what he has accomplished off the court. He is an athlete-turned-academic who broke racial barriers and forged a new path for legions of young people coming up behind him.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared racially segregated schools inherently unequal and, thus, illegal, many public schools and universities in the Deep South remained deeply segregated well into the 1960s. It wasn’t until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that all legally-enforced segregation was abolished. This was merely two years after James Meredith became the University of Mississippi’s first black collegian and one year after Vivian Malone and James A. Hood integrated the University of Alabama.

A comparable movement was occurring at Nicholls State University, under the leadership of then-president, Dr. Vernon Galliano. Founded in September 1948, Nicholls State is nestled along Louisiana Highway 1 on the banks of Bayou Lafourche in Thibodaux, Louisiana. The institution is named for Francis T. Nicholls, a two-term Louisiana governor, Louisiana Supreme Court chief justice, and Brigadier General in the Confederate States Army. Needless to say, in Thibodaux, there was quite a bit of resistance to this change.

Around the same time, in Moss Point, Mississippi, Ira Polk, Hill’s basketball coach at Magnolia High School, was striking a similar tone. Hill says, “His words pretty much were, ‘It’s time for this to be done. Integration is taking place on college and university campuses, and so, if not you, then who? And, if not now, then when?’”

Hill visited Nicholls but, when he arrived, he still was unconvinced that it was the right place for him. It was a conversation that he overheard that served as a watershed moment and, ultimately, his deciding factor for attending the school.

“I heard President Galliano talking to another coach who had brought an African American kid down from Jackson, Mississippi. Dr. Galliano was basically telling him the same thing that Mr. Polk told me,” Hill recalls. “I had two people – one black and one white – both saying let’s get it done.”

But, getting it done would not come without its challenges.

Imagine, for a moment, that you are in Hill’s shoes. It is 1968, 20 years after Nicholls’ founding and some five short months after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. You’re a young Black man, only 18-years-old, who has traveled to the heart of Cajun Country. It is the start of your freshman year of college. You’re filled with all the jitters and nervous anticipation that come with it. Unlike any other student on campus, however, you’ve been tasked with the awesome responsibility of integrating a collegiate athletic program.

That was precisely Hill’s conundrum, and while there were some who wanted to evoke change, there were plenty of others who wanted things to remain status quo.

Hill remembers, “You can’t confine what happened during that time just to the basketball court because I had to go to class, I had to live in the dormitory, [and] I had to go into the town. There would be days I’d think things were moving smoothly and, then, somebody in the classroom would say something that was very racist. It would kind of shatter everything that happened that day. Same thing would happen if I went into town.”

There were also some African American students, clearly unaware of Hill’s plight, who seemed envious of the attention Hill attracted, a disappointment that he, too, had to manage. “It was not just dealing with what happened on the basketball court and, when you’re 18- or 19-years-old, that’s not easy. So, there were just some days and some moments when I wondered, ‘What in the world have I gotten myself into?’”

From the moment Hill stepped on campus and before he ever wore a Colonels jersey, his every move was scrutinized. He was expected to always keep a cool head and exemplify grace under fire – even in the most challenging of circumstances. One such experience came, not from those on the periphery, but from one of Hill’s teammates.

“Because of all the different things that were happening, I always had this feeling that there were some things that were boiling underneath,” Hill says.

Unfortunately, Hill’s instincts proved right. In what should have been a friendly off-season pick-up game, Hill was abruptly confronted with racism from a fellow player.

“I think it was March of ’69. One of my teammates became jealous and he called me the ‘N word.’ I asked, ‘What did you just say?’ He said, ‘You heard me.’ And, he said it again, very blatantly and very loudly. I guess I knew that it could boil over and happen but, after going about 6 months and it had never happened, in my face like it happened, it kind of took me by surprise.”

Hill immediately went to his coach and explained that the behavior was unacceptable and he simply would not stand for it.

“I told him,” Hill recalls, “‘When I came here, I expected this kind of treatment from other teams in the conference – especially the ones that hadn’t integrated. I expected this from fans at some of the other schools. But, I didn’t expect it from my own teammates. Not out loud like that. Not blatantly like that. And, if this is what I’ve got to live with then, hey, I’m leaving here.’”

But, Hill did not leave. In fact, he played basketball for four consecutive years at Nicholls, where after his sophomore season, his teammates named him permanent team captain, the first non-senior to receive the honor. He led the Colonels to their first ever post-season tournament and became the school’s then all-time leading scorer (1,606 points) and rebounder (1,174). Hill was named team MVP for the 1969-70, 1970-71, and 1971-72 seasons. He garnered all-conference, all-Louisiana, and honorable mention All-American selections, as well as being named to the NAIA District 30 All-Star team.

Although Hill was the first player in Nicholls’ history to be drafted into the professional leagues (by both the Seattle SuperSonics of the National Basketball Association (NBA) and the Kentucky Colonels of the now-defunct American Basketball Association (ABA)), destiny had a different path for him. After all, his primary focus was always to be the first in his family to earn a college degree, which Hill did in 1972.

After three years of active duty in the United States Army, where Hill played on the Armed Forces basketball team, conducted basketball clinics for the State Department in Amman, Jordan, and was selected to the All-Army team, Hill returned to Nicholls in 1975 to complete his teacher’s certification. In 1978, he earned a master’s degree in education while teaching at East Thibodaux Junior High School.

In 1979, Hill assumed the role of men’s assistant basketball coach at Nicholls under Coach Jerry Sanders. He remained on the coaching staff until 1985 as an assistant to Coach Gordon Stauffer.

Despite his love for basketball, Hill did not like spending so much time away from his home and young family. He received an offer to go back to teaching, this time in Nicholls’ health and physical education department. This role became the catalyst for Hill’s lifelong journey in educational leadership. After earning a doctorate in education in 1993, Hill again made history at Nicholls as the school’s first black administrator when, in 1999, he was named the Dean of the College of Education.

After seven years as dean and over 25 years of service, Hill retired from Nicholls. Subsequent to his retirement from Nicholls, he was honored with the title of Professor Emeritus.

Since leaving Nicholls in 2008, Hill has been principal of the MAX Charter School and now serves on three charter school boards of directors and the board of Thibodaux Regional Medical Center. Currently, he is an associate professor of educational leadership at the University of Holy Cross in New Orleans.

Hill’s love for education likely comes from the many teachers and coaches who inspired him and took an active interest in his upbringing. People like Goslin Ward, his first high school basketball coach who bought Hill his first pair of Converse. Roy Banks, who talked to Hill and his classmates about life. Carlton Reese, the head football coach who taught Hill driver’s education and was the first man who uttered the words, “I’m proud of you, Son.” Dr. Donald Ayo, former president of Nicholls, who was instrumental in Hill becoming Dean of Education. And, of course, Ira Polk whose influence made Hill’s trek to Nicholls possible.

There is a certain irony in both the literal and metaphoric transition from Magnolia High School Monarch to Nicholls State University Colonel. Lesser men would have crumbled under the weight of such responsibility. It was certainly not a job for the faint of heart; yet, Hill found a way to persevere – to demonstrate a winner’s attitude and remain a team player – despite the turbulence of the times.

Hill remarks, “I remember something that Steve Jobs said when he gave a commencement address at Stanford University. ‘You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards.’ In other words, perspective is only achieved retrospectively. When I was 18-, 19-, and 20-years-old, I had no perspective. I wanted to get a college degree and that’s all I knew. The significance of coming to Nicholls State University – a predominantly white institution – was lost on me. But now, 50 years later, looking back, I have a different perspective on it. If what was done has paved the way for some others coming along, just like some of the people who are long forgotten paved the way for me, then yeah, it was very significant.”

Originally, Hill was somewhat uncomfortable with the idea of being this year’s Mr. Louisiana Basketball award recipient. “I looked at the people who had won it before like Dale Brown and Joe Dean and I felt like, ‘I don’t deserve this award. I haven’t been an active promoter of basketball across Louisiana.’”

Dumbfounded, Hill reached out to his former coach, good friend, and mentor, Don Landry, the 1980 Mr. Louisiana Basketball award recipient, who told Hill, “Your influence has been greater than you can ever imagine. Your influence has helped a lot of people along the way; so, don’t feel like you are not deserving of this award.”

Hill is humbled by the recognition of his peers and contemporaries who, like him, love the game of basketball. “It’s always good to be recognized for things for which you don’t even think you deserve to be recognized,” he says. “So, hey, in that sense, it is a good award for me – probably one of the best that I’ve ever received.”

Indeed, in 50 short years, Hill has made a tremendous contribution to both basketball and academia. He committed to and has demonstrated that student-athletes have the power and wherewithal to make lasting contributions to society, even without playing professional sports.

“As much as I appreciate this being a basketball award, I’d like to emphasize the fact that an athlete was able to get three college degrees. An athlete was able to become a college dean. An athlete was able to become a Professor Emeritus. I think that, if there is any kind of lasting legacy to all of this, I would want kids to know that the things that I learned in sports and athletics helped paved the way for me to achieve those other things in academics. If they would just apply what they learn in sports and athletics – the hard work, time management, and organizational skills – it can propel them to have successful careers and successful lives, also.”

In addition to honoring Hill, the May 5 awards banquet will include the induction of former McNeese State University and Southeastern Louisiana University coach E.W. Foy and former Louisiana Tech University coach Tommy Joe Eagles into the Louisiana Basketball Hall of Fame. There will also be recognition of Louisiana’s major college, small college, junior college and high school players and coaches of the year, along with the top pro player from the state. More information about the LABC can be obtained by visiting their website at www.labball.com.

- < PREV LHSAA Baseball Playoff Update: Curtis and Catholic seek closeouts, Kentwood advances, more series start Friday

- NEXT > Big weekend on horizon for area college baseball teams