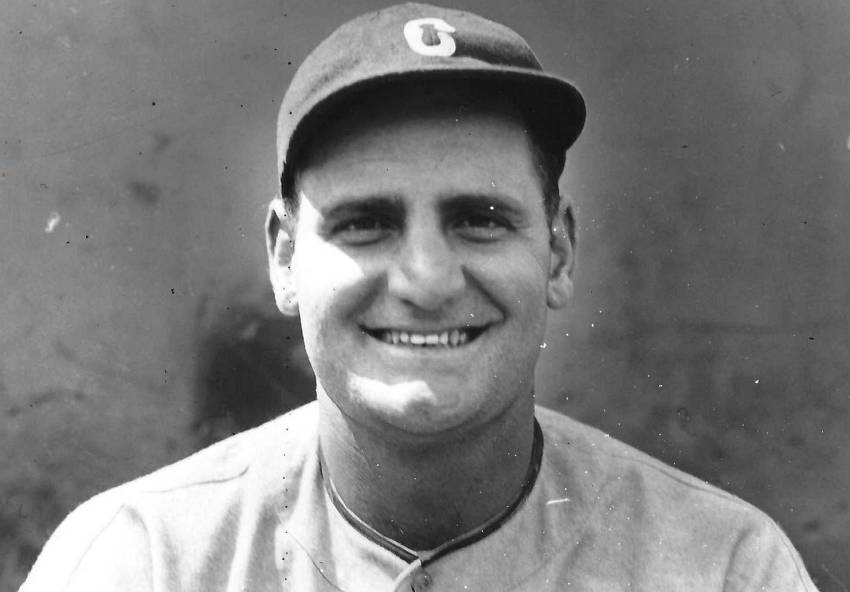

Former New Orleans major leaguer Zeke Bonura an offensive threat in 1930s

Sportswriter Furman Bisher of The Sporting News once wrote about former major leaguer Zeke Bonura, “He played what was known as a stationary first base. Neither he nor the bag moved. He hit a ton but fielded as if he had another ton on his back.”

The writer’s sentiment fairly summed up Henry “Zeke” Bonura’s major-league baseball career. From 1934 to 1939, he was one of the most productive hitters in the majors. But at the same time, he had a reputation as a defensive liability as a first-baseman.

Bonura was born in New Orleans in 1908. His father and relatives owned the Vaccaro Brothers Steamship Line and a large fruit and vegetable distribution company in the city, a factor that would later play into one of Bonura’s nicknames. He attended St. Stanislaus College, a preparatory high school in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, where he became a standout athlete in baseball, basketball, football, and track and field, serving as captain of each of his teams. For a time, he held the American record for javelin throw, established at an A. A. U. track meet in San Francisco in 1925.

He acquired the nickname “Zeke” from one of his St. Stanislaus teammates who exclaimed, “Look at that huge physique,” as Bonura was dressing for a football game. The moniker stuck with him the rest of his life.

Bonura attended Loyola University in New Orleans for two years, where he continued his athletic prowess. He and football teammate Marmont Schwartz had planned to continue their gridiron careers at Notre Dame. But after a tryout with the local New Orleans Pelicans baseball team, he decided to pursue a baseball career instead.

The 20-year-old right-handed hitter was an immediate success in 1929 with the Pelicans, who were managed by New Orleanian Larry Gilbert. Bonura batted .322 in 131 games for the third-place club. After hitting .359 in 85 games in his third season with the Pelicans, he was sold to Indianapolis for the rest of the season.

Bonura was again sold after the 1931 season to Dallas in the Texas League. The husky, 6-foot, 200-pounder developed a power stroke with the Steers, hitting 45 homers over two seasons. He was the voted the league’s Most Valuable Player in 1933, leading in home runs, RBIs, and runs.

He joined the struggling Chicago White Sox in 1934. After winning only four of its first 15 games, third baseman Jimmie Dykes also assumed the role of manager, replacing Lew Fonseca. Bonura was one of the bright rookies that came into the league that season. He led the last-place White Sox with 27 home runs (a new club record) and 110 RBIs while batting .302. He was a popular player with his teammates and the Chicago fans, who were desperate for something positive with the struggling team. Bonura was famous for bringing his teammates bananas from his father’s business and was aptly referred to as “Bananas” Bonura.

For three consecutive seasons beginning in 1935, Bonura was a holdout in signing his contract with the White Sox. He believed he deserved higher salaries than the ones offered, based on his offensive contributions to the team. His holdouts delayed his getting in shape for the upcoming season, situations that aggravated Dykes. They developed a “love-hate” relationship—Dykes loved Bonura’s bat in the White Sox lineup but hated the disruption Bonura caused each spring.

Bonura established himself as one of the leading hitters in the league. In 1935, he batted .295 with 21 home runs and 95 RBIS. Despite not being in shape at the start of the 1936 season, due to his holdout, he responded with a .330 batting average, 12 homers, and 138 RBIs (fourth in the American League in 1936 and still third all-time in White Sox history). 1937 saw him hitting .345 (fourth in the American League) with 19 home runs and 100 RBIs. During his first four seasons with the White Sox, he averaged only 28 strikeouts per year.

While Bonura’s fielding percentage as first baseman wasn’t below average, he was criticized by Dykes and sportswriters for allowing ground balls to get past him at first base. He was slow and immobile around the bag. His defensive play would become the biggest criticism against him in an otherwise prolific major-league career.

Bonura ultimately fell out of favor with Dykes, who had him traded to Washington for first baseman Joe Kuhel before the 1938 season. It was an unpopular move with Chicago fans, since Bonura owned the Windy City because of his play and his personality.

Bonura’s batting average dropped 56 points with the Senators in 1938, but he continued to display a powerful bat with 22 home runs and 114 RBIs. (He was the Senators’ single-season home run leader until Roy Sievers surpassed him in 1954.) But his fielding struck a sour note with the Senators’ front office, and they dealt him to the New York Giants, where he played with fellow New Orleanian Mel Ott in 1939. He led the Giants in batting average (.321) and RBIs (85) that season.

Following a season split between Washington and the Chicago Cubs in 1940, Bonura became eligible for the military draft. He was the leading hitter for the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association in June 1941 when he was inducted into the Army. He was assigned to Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, as an assistant to the athletic officer. However, the 32-year-old Bonura was discharged later that year because of the Selective Service 28-year age rule.

Bonura was recalled into the Army in January 1942, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He spent 20 months in North Africa where he was awarded the Legion of Merit medal by General Dwight Eisenhower, for his leadership in organizing GI baseball teams and leagues. He became known as the “Judge Landis of North Africa.” He was later stationed in Europe, where he continued to organize and promote baseball events for the troops.

After missing four baseball seasons during World War II, Bonura returned to baseball in 1946 at age 37. He went back to Minneapolis as player-manager, but he lasted less than a month before being released. He finished out the season as player-manager with Thibodaux in the Evangeline League. He managed eight more seasons with several teams in the low minors, finally calling it quits after the 1954 season.

His major-league career stats included an impressive .307/.380/.487 batting line, 119 home runs, and 704 RBIs in seven seasons.

One of the finest all-around athletes from Louisiana, Bonura was inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame in 1989 and the New Orleans Diamond Club Hall of Fame in 1966.

Bonura remained a popular figure in New Orleans after his baseball career was finished. Terry Alario Sr., a former West Jefferson High School, American Legion, and Northwestern State pitcher in the 1960s, recalls being coached by Bonura in an All-American Baseball League all-star game in 1967. Alario said, “I mostly remember his sense of humor and his unbelievable knowledge of baseball. Listening to him was like opening an encyclopedia.”

Bonura was frequently remembered in local newspaper sports columns for his on-the-field achievements and his colorful personality. Long-time Times-Picayune sports editor Bob Roesler wrote in 1969, “Baseball needs more Zeke Bonuras to liven up the action.” Bonura died in 1987 at age 78.

- < PREV Baseball Playoffs: Lutcher advances, Doyle wins, DLS eliminated Friday

- NEXT > REPLAY: John Curtis uses two big innings to down Rummel to advance to semifinals

Richard Cuicchi

New Orleans baseball historian

Richard Cuicchi, Founder of the Metro New Orleans Area Baseball Player Database and a New Orleans area baseball historian, maintains TheTenthInning.com website. He also authored the book, Family Ties: A Comprehensive Collection of Facts and Trivia About Baseball’s Relatives. He has contributed to numerous SABR-sponsored Bio Project and Games Project books.